Rare Disease, Common Pattern

On failed Osteogenesis Imperfecta drug trials, conflicted endpoints, and the pharmaceutical companies who will sunset us

It’s rarely a good sign when a company elects to make a big announcement on December 26 and this held true for a major research announcement related to the treatment of Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI), my disability. Ultragenyx, partnered with Mereo BioPharma, shared with stakeholders that their experimental OI treatment ,setrusumab, didn’t reduce fractures any more than placebo (no medication) or IV bisphosphonates, which are the current gold standard of care but not quite considered a true treatment1. This surprising and disappointing outcome was consistent for both studies (named ORBIT and COSMIC); One included 159 people with OI between ages 5 and 25, and the other included 69 patients between the ages of 2 and 7; the latter group compared setrusumab to IV bisphosphonates.

What is Setrusumab?

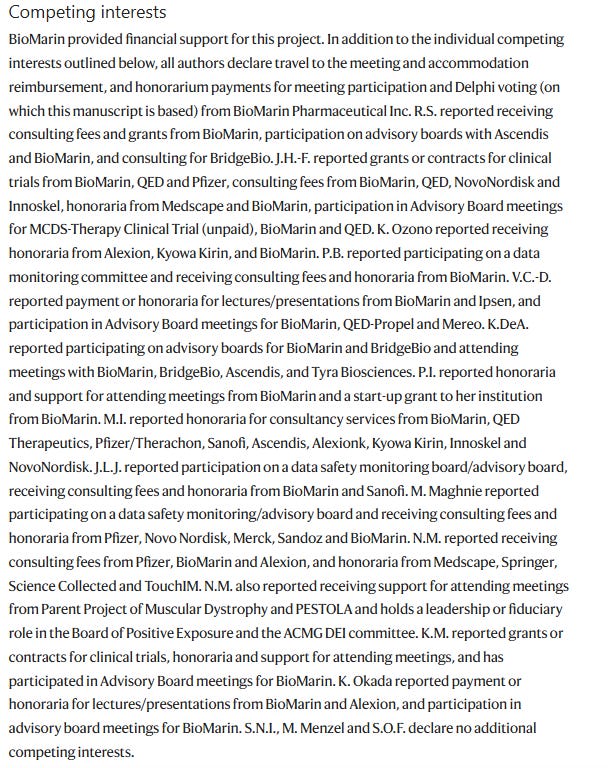

This is possibly the biggest OI drug treatment news in decades but let’s catch up because this isn’t exactly covered on the nightly news. To understand what's at stake here, you need to know that setrusumab represented a fundamentally different approach to treating OI compared to what’s been tried before. For decades, the main treatment option for OI has been IV bisphosphonates - drugs that slow down bone breakdown. Bisphosphonates can increase bone density, but they don't actually help our bodies build stronger bone, which is why they're considered management rather than true treatment. Setrusumab is an anti-sclerostin antibody, meaning it's supposed to actively promote bone formation rather than just putting the brakes on bone loss. This distinction matters enormously. The research to study setrusumab’s safety and efficacy (does it work) began around 2018, fueled by pharmaceutical companies recognizing that whoever cracked the code on OI treatment first would have an uncontested market of people desperate for something better than what we've got.

ORBIT and COSMIC were both studying setrusumab in slightly different ways. While both studies failed to show a reduction in fracture rate-which is usually considered the most common patient-centered outcome for OI (more on that later), both studies did result in statistically significant improvements in bone density in the femur and spine2. Whether this results in any meaningful changes for patients isn’t clear. A mantra I’ve heard repeated in our community (which admittedly doesn’t always mean it’s accurate!) goes something like, “More bone can be a good thing, but it’s still OI bone.” Our bodies are programmed to build bone in an inefficient way.

Why is OI making the news?

It’s been somewhat fascinating to watch the coverage of these clinical trial failures by journalists who cover health stocks and pharmaceutical advancements. Their alarmist word choices make it clear that this is.not.good. One analyst urged others to “sell the Osteogenesis Imperfecta Dip”. Another journalist covering healthcare stocks used the pun that “hopes fracture” with these trial fails. In July, this outlet conveyed continued confidence despite warning signs that the drug might not be working as well as hoped. OI has made headlines in outlets like MarketWatch, Bloomberg, Yahoo, Barron’s, and Reuters, but none of this coverage indicates any care for people with OI.

The story being told isn’t about people, it’s about money. Stocks for Ultragenyx and Mereo have “plummeted” by 45% and 90%, respectively. These companies were banking on massive profits in a market with no competition. It was estimated that the US could see $450 million in sales of setrusumab by 2035. The possibility of that profit has served as a driver for investors, but we shouldn’t overlook the other end of the scale, which is the cost to get this drug to actual people with OI. Drugs like these regularly cost hundreds of thousands of dollars per year per patient. With that enormous cost in mind, it’s in all of our best interest to ensure these drugs actually work and fulfill the promise they make.

What can we learn from other (messy) drug trials?

So let’s get to that promise. Before they start, clinical trials studying whether drugs work or not have to choose what they’ll measure to make that determination. That point of focus or measure is called an endpoint. While they sound rather dry, endpoints are extremely important. They’ve been the source of controversy in research focused on a goal or goals that differ from what patients prioritize.

Vosoritide (voxzogo), made by BioMarin, is another blockbuster drug intended to treat people with a different form of skeletal dysplasia, achondroplasia. It’s global sales topped $735 MILLION in 2024, which was a 56% increase from the year before. At least some of that increase might be due to these clinical guidelines that recommend all infants with achondroplasia start the drug as soon as possible after birth3. What shocked me most about these guidelines was the GLARING financial conflicts of interests of the authors. I was fired up enough to publish a reply to the guidelines with colleagues4. A whopping 75% of the authors of these guidelines have direct financial ties with the drug company that produces the drug they just recommended to every infant with achondroplasia. Take a quick scan of their reported competing interests and notice how many times BioMarin is listed.

Yes, the authors reported these ties, but merely reporting a conflict of interest doesn’t make it go away. The high rate of conflicted clinicians was worrisome enough but maybe there was hope. Had the consensus group meaningfully included patient advocates? No. The guideline group had also conveniently avoided the world’s longest-standing patient advocacy group for people with achondroplasia and other forms of dwarfism, Little People of America, in its consensus-making process. Instead, the consensus group that developed these guidelines included a small patient advocacy group from Spain and what many consider a shell company staged as a skeletal dysplasia advocacy group whose primary aim is to encourage people to consider limb lengthening surgeries. Not exactly the behavior of a group with aims to encourage authentic patient engagement. Messy.

Back to endpoints.

The primary endpoint for all voxzogo clinical trials was “change from annualized growth velocity”, otherwise known as height. In contrast to this news on the COSMIC and ORBIT trials, Biomarin did hit their goals to show significant change in people who took their drug compared to those who took a placebo. Even with that, questions remained: Did what changed matter? Patient advocates had been saying for years that, “Growth velocity is not addressing the actual health and quality of life issues of people with dwarfism.” People have also questioned whether a drug’s ability to increase height by 6 inches over a lifetime is meeting an unmet medical need (at a cost of $320K per year per patient). Biomarin, the pharmaceutical company that produces voxzogo, had conducted focus groups and conducted outreach to the achondroplasia community but in the end, they’d failed to listen to what was most important to people with achondroplasia for a drug to address. For years, people with achondroplasia have voiced a need for better treatments related to spinal stenosis, joint disintegration, sleep apnea, and skull base narrowing. We can’t know if any of these symptoms are improved by voxzogo because these symptoms weren’t chosen as endpoints for voxzogo research and in most cases, weren’t even measured by the pharma companies leading the research.

Where do we go from here?

I’m far from a cure seeker or drug chaser. I still remember my private realization-up late alone reading research- that the “cure” for Osteogenesis Imperfecta that many marvel about isn’t addressed at decreasing our symptoms or strengthening our bones at all. A true cure will be more likely to be brought about by gene editing. It won’t strengthen bones but it will initiate a planned eradication of future people born with OI. When people talk about a cure, they usually mean curing the future of people like me rather than curing me of the painful, limiting, and frustrating parts of OI. Individual feelings and beliefs about cures are highly variable, personal, and (usually) private.

That said, it also shouldn’t come as a surprise that I’m a huge fan of, believer in, and practicing scientist of RESEARCH.

Osteogenesis imperfecta research is immeasurably valuable because there remains so much about this mysterious condition that we just don’t understand.

In the last few years, it’s been a win for us that major pharmaceutical companies have agreed and bought into the bandwagon that offers gigantic profit potential in the race to find the first true treatment for our condition. Setrusumab seemed to point to that promise.

This brings us back to our stalled OI drugs. The reduction of fracture rate, aka fewer broken bones, IS something the vast majority of our OI community very much wants. In that regard, it makes sense that Ultragenyx and Mereo selected fracture rate as their primary endpoint. But science-nor life-takes place in a vacuum. Any person with OI will tell you that when-and maybe more mysteriously-when we don’t fracture doesn’t always make sense. For some of us on any given day, we can sneeze too hard and break a rib but take a fall and emerge unscathed. While not well documented, “fracture cycles”5 are certainly a phenomenon discussed in our community, where people find themselves breaking bones repeatedly until at last they seem to plateau. There’s also the reality that not fracturing doesn’t always mean milder presentations of OI. Some kids and adults with OI fracture because they are very physically active. Others fracture very infrequently because they are very sedentary. While fracture rate would seem a clear and very important thing to measure, it brings its own unique complexities-especially for a timeframe as short as 18 months and a sample size of just 159 and 69. Ultragenyx spokesperson noted that the fracture rate for the placebo group (the group that didn’t get the drug or any treatment) was very low during the 18 months of the study. This lowered baseline made it even more difficult for the drug to demonstrate effectiveness, not necessarily because the science was flawed, but because fracture rate in people with OI isn’t something we totally understand.

I’m not among the stock shareholders who will lose untold sums with this “failure” and I’m in what sometimes feels like the minority of healthcare researchers who doesn’t receive or accept honorariums from pharma.

Our losses, as members of the OI community, are unfortunately more consequential. All signs indicate Ultragenyx and Mereo (the only pharma companies working on anything related to our rare disease) will “sunset their OI programming.” In contrast to the messiness of Biomarin’s involvement with the achondroplasia community, I applaud Ultragenyx and Mereo’s involvement with our OI community during these trials. While I’ve discussed the complexities of fracture rate as an endpoint, I do admire their commitment to selecting an endpoint representative of what our community cares about most. It’s also notable that these companies got to know our community in what seemed like honest and engaging ways. They partially supported conferences and engaged in these spaces with respect not intrusion. From my observations, Ultragenyx and Mereo have largely been upstanding collaborators with our community. It’s possible they’ve worked with some of the many companies that serve as bounty hunters for people with rare disease (that I’ve written more about here) but this also seems a broader problem, not specific to any one or a few pharma companies.

While I’ve been relatively impressed with Ultragenyx and Mereo so far, what happens next will be no less disappointing. It’s critical to never forget that our best interest is NEVER their priority. It is always profit. Just as a developer who renovates a historic building, draws community members in with promises of revitalization, then abandons the project when the luxury condos don’t sell - leaving behind raised expectations and an empty shell - the writing is already on the wall that Ultragenyx and Mereo will move on.

What happens next matters. When Ultragenyx and Mereo move on to invest in treatments for Angelman syndrome and other more profitable conditions, they’ll take with them not just their funding but also the infrastructure, momentum, and hope they generated. Their financial support for OI research organizations and patient registries will likely dry up alongside their stock prices.

Here’s what I wish pharmaceutical companies knew

Fracture rate isn’t the only endpoint that matters to us. Pain - chronic, acute, breakthrough pain that current medications barely touch - shapes our daily lives in ways fractures don’t capture. Fatigue limits what we can do and for how long. Progressive bowing affects mobility and function. Many of us are rightfully fearful of respiratory illness as we’ve known community members who have died from the flu, Covid, or pneumonia. Research has confirmed that respiratory illness is a leading cause of death for people with OI6. These outcomes don’t make for clean 18-month studies with binary results, but they’re what we live with.

And honestly? Some of the most meaningful investments wouldn’t be OI-specific at all. We desperately need better pain medications - options beyond the limited and often stigmatized choices we have now. We need research into bone pain mechanisms that could benefit multiple conditions. We need pharmaceutical companies to recognize that rare disease communities aren’t just potential markets to be exploited during profitable moments and abandoned when the numbers don’t work out.

The setrusumab trials taught us something valuable, even in their failure: fracture rate in OI is more complex and mysterious than a simple count suggests. That knowledge matters. What happens with it next - whether it informs future research or gets buried in a “sunset” program - will tell us everything we need to know about whether pharmaceutical companies see us as partners or just profit centers.

Ralston, S. H., & Gaston, M. S. (2020). Management of osteogenesis imperfecta. Frontiers in endocrinology, 10, 924. Available here: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/endocrinology/articles/10.3389/fendo.2019.00924/full

Glorieux, F. H., Langdahl, B., Chapurlat, R., De Beur, S. J., Sutton, V. R., Poole, K. E., ... & Javaid, M. K. (2024). Setrusumab for the treatment of osteogenesis imperfecta: 12-month results from the phase 2b asteroid study. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 39(9), 1215-1228. Available here: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39012717/

Savarirayan, R., Hoover-Fong, J., Ozono, K., Backeljauw, P., Cormier-Daire, V., DeAndrade, K., ... & Fredwall, S. O. (2025). International consensus guidelines on the implementation and monitoring of vosoritide therapy in individuals with achondroplasia. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 21(5), 314-324. Available here: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41574-024-01074-9

Schelhaas, A., Ayers, K., Meredith, S., Smith, L., & Stoll, K. (2025). Ensuring diverse representation and minimizing conflicts of interest in clinical practice guidelines. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 1-2. Available here: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41574-025-01122-y

Nijhuis, W., Verhoef, M., van Bergen, C., Weinans, H., & Sakkers, R. (2022). Fractures in osteogenesis imperfecta: pathogenesis, treatment, rehabilitation and prevention. Children, 9(2), 268. Available here: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9067/9/2/268

Folkestad, L., Hald, J. D., Canudas‐Romo, V., Gram, J., Hermann, A. P., Langdahl, B., ... & Brixen, K. (2016). Mortality and causes of death in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta: a register‐based nationwide cohort study. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 31(12), 2159-2166. Available here: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jbmr.2895

Kara I don’t know much about OI. Thanks for the introduction. I’m also a research champion and skeptic. I echo your advocacy for sustainable partnerships for research that matters to studied communities. You point out the flawed business model that only considers short term profitability as success, the more massive the better. I’m a founder of a startup seeking funders/investors who can think longer term for modest gains. I’m learning about crafting campaigns do build progressive support from the ground up. I will continue to follow your community’s research journey.